I, Dean Haley (True Blue Bees, Brisbane ANBA), accompanied by Stephen Brownlie (Brisbane ANBA) journeyed to Brewarrina in north western NSW to donate Austroplebeia australis logs, educational signage, and books to the Brewarrina Aboriginal Cultural Museum. We met with Brad Harding & other museum staff, and my local Brewarrina contact Brad Steadman. It was Brad’s idea to bring these bees to Brewarrina, to educate people and as another attraction in the town. The ANBA generously supported the venture by sponsoring fuel money, which is not cheap these days.

Bees and honey are found in names of places, as well as dreamtime stories of the local area.

Brad Steadman, a languages and cultural officer at REDI (Rural Enterprise Development Institute), tells a tradi-tional story of Baiame (a creation being) chasing a bee with a feather attached to its abdomen from Cobar towards Louth, 200km SW of Brewarrina. Catherine Langloh Parker relates the Narran Lake people, Noongah Burrah story of Narahdarn the Bat (published 1896) which mentions a bee tree with honey. Narran Lake is a wetland located 50km east of Brewarrina. Further south, the town name Narromine means “Place of many bees” in Wiradjuri.

Although I could not find australis bees on flowers during my short stay, or find a nest, I believe they still occur naturally in Brewarrina as I observed a syrphid fly (Ceriana ornata) which is a natural predator associated with stingless bee nests. The suitability of the area is also supported by two australis specimens collected by Dr Michael Batley (Australian Museum) in 2005, one 30km east of Cobar, and the other near Lightning Ridge www.biocache.ala.org.au/occurrences

Brewarrina is my Mum’s home town, and I spent much time there as a boy talking to uncles about many cultural and natural things, and it’s the place I first learned about stingless “bush bees”. My uncle John Steadman’s detailed (and highly accurate) descriptions of australis life and habits fascinated me, and eventually led to me keeping these bees as an adult, engaging with other native beekeepers, helping establish the ANBA, helping organise native bee conferences, and writing a native bee book. Taking bees and educational material to the cultural museum therefore was a “closing the circle” moment, and a chance to share some of my knowledge with the community.

Steve and I spoke with Brad Steadman about how bees fit in traditional society. The local Weilwan, Ngemba speaking people are a maternal society, tracing their ancestry through their mothers lineage, with the kinship system divided into quarters. The quarters encompass all living things, including animals, birds, fish, insects, and plants. People establish a deep understanding of those living creatures assigned to their quarter, and are expected to learn the natural Lore and rhythms of those creatures. Bees therefore are part of the natural system of life, and appreciated for the role they play. As the Barwon river, connecting rivers and wetlands are the life-blood of this semi arid region, the bees are expected to be adapted to, and interact with the riverine system.

Brewarrina has incredible cultural and historical significance. The national heritage listed fish traps (Baiame’s Ngunnhu) on the Barwon river may be as old as 40,000 years, and may represent the world’s earliest manifestation of complex thinking and large scale planned construction. The fish traps were an incredible food resource in traditional life, and resulted in the area becoming a meeting place for tribal business and celebrations. This included peoples from many different language groups, who would travel long distances to attend these meetings. The cultural museum is built on the banks of the Barwon overlooking the ancient fish traps. The domed construction of the museum is reminiscent of a cave, and displays cultural and historical artifacts. The grounds of the museum are planted with bush medicine plants, therefore the native bees will fit well, as they are also regarded as bush medicine.

Brad Steadman has been teaching Brewarrina Primary School children about bees and other insects. Last year, this culminated in honey tasting, and a trip to nearby bushland to taste bush tucker and learn about bush medicine plants. One child stated that the honey tasted like it had pineapples in it, which was his way to describe the sweet & sour tones of native honey.

There are plans to hold a bee celebration at the museum on 1st Sep 2023 (“Bee in Bre in 23”), where there will be talks, BBQ, and native honey on damper. Any ANBA members attending will find plenty to see and do in picturesque and historical Brewarrina. We also spoke with a representative from the Brewarrina Local Aboriginal Land Council, who are interested in installing log colonies in a planned community garden. Other locals expressed interest in purchasing boxed hives for their gardens.

Mount Kaputar

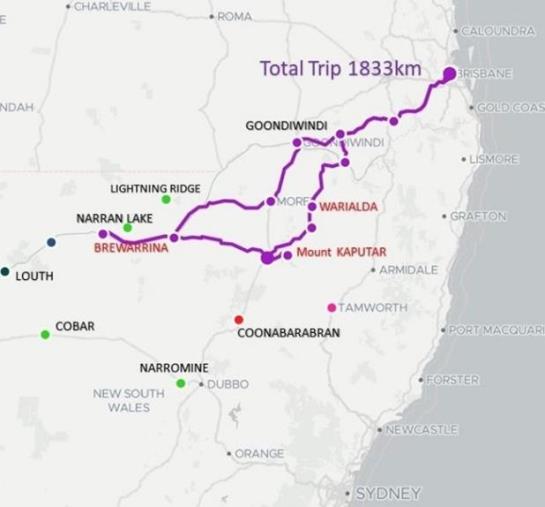

After a couple of days in Brewarrina, Steve and I travelled to Mount Kaputar which is located near Narrabri in NSW to look for T. carbonaria. I was intrigued by an occurrence report from nearby Moama national park (Atlas of Living Australia website www.ala.org.au ). During the 4 hour road trip we became very aware of the changes that modern agriculture had made to the landscapes. Wheat and cotton farms were either treeless, or retained scattered trees, or trees on fence rows and small patches separated by many kilometres of grassland. Steve and I concluded that stingless bees would find it impossible to migrate across these grassy barriers. Localised extinctions of stingless bees in an area (from drought, flood or fire) therefore, would likely be permanent as the natural migration pathways are now destroyed.

Tetragonula carbonaria are common in well watered coastal areas of NSW and QLD but are less prevalent in areas to the west of the Great Dividing Range, though populations have been reported near Goondiwindi (A QLD border town), near Tamworth, and possibly Coonabarabran.

Mount Kaputar is an interesting and biodiverse environment. Towering 1510 metres above the plains, it is of volcanic origin, thrust upwards around 20 million years ago. This mountain is the most north-western Australian mountain that experiences snow, with a large forest of Snow Gums. The height of the mountain creates its own weather, and the climate and vegetation change into distinct zones as you climb into the colder, wetter and higher areas. The slopes below 800m are very dry, with stunt-ed pine trees and scrub. As you climb higher, 800 to 1000 metres, the moisture supports a cooler climate Grey Box forest. There are diverse plant species, and large trees with some hollows. We would have loved to search this area longer as it seemed suitable for carbonaria.

Above 1300 metres, the plants are adapted to subalpine cold conditions. Stands of Snow Gum, Mountain Gum, and Ribbon Gum tower to 30 metres tall. The understory in this high forest was well developed and everything, everywhere was in flower, and covered everywhere in large numbers of pollinators. I was amazed at the sheer diversity of large, colourful flower visiting flies with some flies half the size of my thumb. There were also butterflies, beetles, and solitary bees! It took me an hour and a half to complete an “easy” 2km walk, as I stopped every three steps to photograph new and unfamiliar bees. I think this is a bee diversity hotspot and would recommend the area to a proper bee researcher. They would want to take a good camera with them, as the hundreds of photos I took on my mobile phone resulted in only a few with acceptable clarity, and part of the problem was the very tiny size of many of the bees I saw.

A reed bee, common from Mt Kaputar subalpine zone with brilliant coloured abdomen.

Acknowledgement and contributions: Australian Native Bee Association – Fuel money, Steve Brownlie – Use of his vehicle, Tony Harvey (Wide Bay Stingless Bees) – reasonably priced log colonies. Thank you to my cousin Brad Steadman – for coordination and communication with the museum and the land council.

Note: The log hives donated to the museum were ethically sourced from semi-arid locations in QLD where they were destined for destruction during land clearing. The bees then resided in Brisbane for a couple of years be-fore their long journey to Brewarrina. It is my strong recommendation that bees be respected, and not harvested from the forest.